Shooting Ghosts

A U.S. Marine, a Combat Photographer,

and Their Journey Back from War

"Brennan and O’Reilly strip away any misplaced

notions of glamour, bravery, and stoicism to craft an

affecting memoir of a deep friendship"

-Publisher's Weekly

Available now

from Viking Books, an imprint of

Penguin Random House

Shooting Ghosts

A U.S. Marine, a Combat Photographer,

and Their Journey Back from War

"Brennan and O’Reilly strip away any misplaced

notions of glamour, bravery, and stoicism to craft an

affecting memoir of a deep friendship"

-Publisher's Weekly

Available now

from Viking Books, an imprint of

Penguin Random House

A unique joint memoir by a U.S. Marine and a conflict photographer whose

unlikely friendship helped both heal their war-wounded bodies and souls

.

"A courageous breaking of the code of silence to seek

mental health for veterans and the war-scarred."

-Kirkus Review

.

"A courageous breaking of the code of silence to seek

mental health for veterans and the war-scarred."

-Kirkus Review

▼

The Authors

Finbarr O'Reilly

and

Thomas James Brennan

▼

The Authors

Finbarr O'Reilly

and

Thomas James Brennan

▼

Finbarr O'Reilly spent 12 years as a Reuters correspondent and staff photographer based in West and Central Africa and won the 2006 World Press Photo of the Year. His coverage of conflicts and social issues across Africa has earned numerous awards from the National Press Photographer's Association and Pictures of the Year International for both his multimedia work and photography, which has been exhibited internationally. Finbarr spent two years living in Congo and Rwanda and his multimedia exhibition Congo on the Wire debuted at the 2008 Bayeux War Correspondent's Festival before traveling to Canada and the US. He embedded regularly with coalition forces fighting in Afghanistan between 2008-2011 before moving to Israel in 2014, where he covered the summer war in Gaza from inside the Strip. He is a 2016 MacDowell Colony Fellow and a writer in residence at the Carey Institute for Global Good, a 2015 Yale World Fellow, a 2014 Ochberg Fellow at Columbia University’s DART Center for Journalism and Trauma, and a 2013 Harvard Nieman Fellow. He is among those profiled in Under Fire: Journalists in Combat, a documentary film about the psychological costs of covering war. The film won a 2013 Peabody Award and was shortlisted for a 2012 Academy Award. He is currently based in London.

Thomas James Brennan is a retired Marine Corps sergeant who served in Iraq during the Second Battle of Fallujah, and as a squad leader in Afghanistan’s Helmand province with the First Battalion, Eighth Marines. He was medically retired in December 2012 and is a member of the Military Order of the Purple Heart. Since 2012, he has turned to journalism and in 2016 founded The War Horse, a nonprofit investigative newsroom. In March 2017 he broke the nude photo sharing scandal in the military, forcing Pentagon and Congressional investigations that have changed legislation about sexual exploitation across the Department of Defense. Brennan profiled Medal of Honor recipient Kyle Carpenter for Vanity Fair and has been a regular contributor to The New York Times At War blog. His work for At War earned him a 2013 Honorable Mention from the Dart Center at Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism. Brennan was the military affairs reporter at The Daily News from early 2013 through mid-2014, when he was accepted to the Stabile Center for Investigative Journalism at Columbia's Graduate School of Journalism. He earned his Masters in Journalism in May 2015. He won the 2014 American Legion Fourth Estate Award for exposing how government sequestration in 2013 hindered mental health care at Camp Lejeune, N.C. and at U.S. military bases worldwide, prompting then-secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel to restore staffing and treatment to full capacity across the Department of Defense. Brennan is based in Jacksonville, N.C.

▼

OP kunjak

OP kunjak

Musa Qala District

October, 2010—OP Kunjak is a tiny combat outpost perched atop a hill. The base is named after an adjacent village and offers views stretching across the sun-bleached pebbles of a wide riverbed, or wadi, and over an undulating expanse of barren landscape. To the north, a triangular mountain looms above the dark outline of more distant peaks.

The dead autumn scenery allows only shades of brown. Warm desert winds blow gusts of fine moon-dust over the outpost and through sparsely populated villages below. Each village is a scattered maze of mud-mortared walls and compounds hunched thick and low to the ground — sturdy Afghan fortresses built to keep intruders out. OP Kunjak is designed to do the same, but apart from its elevated hilltop position, the lines of defense are bone thin.

The outpost is about the size of three basketball courts ringed by a wall of Hesco barriers — squat blocks of thick cloth and steel wire filled with earth that stand shoulder high and just as wide, and function as blast walls when stacked side-by-side.

Coils of razor wire crown the Hesco walls while Marine sentries stand watch around the clock from behind 0.50-caliber machine guns mounted on three sand-bagged lookout posts. For Sgt. Brennan and about two dozen men from the First Battalion, Eighth Marines, OP Kunjak will be home for most of their seven-month deployment to Helmand, Afghanistan's largest province, and the war’s deadliest.

▼

Helmand Province, Southern Afghanistan

Helmand Province, Southern Afghanistan

▼

combat patrol

combat patrol

Finbarr

October 23, 2010—We're moving up a narrow alleyway about half an hour into the patrol when a machine gun muzzle flashes from a corner about 150 feet ahead of us. The curved alleyway is two blocks long with high mud walls and it's barely wider than a car. We are stuck half way along it with only the wall’s contour as cover. The machine gun sounds like one of the Russian-made, belt-fed PKMs favored by the Taliban and capable of firing 650 rounds per minute. Our attacker fires in controlled bursts, ricocheting bullets off the wall in an effort to strike us. There's no way to move forward or back along the alley without getting hit. We're pinned down.

Marines break “contact” by moving. Remaining static is the worst thing to do in a firefight. Brennan radios in a contact report and orders one of his men to fire a 40mm fragmentation grenade toward the attacker’s position. Lance Corporal Dustin Moon kneels in the middle of the alley under a burst of covering fire and lobs the grenade forward. As an embedded photographer and a non-combatant, I concentrate on taking pictures as bullets gouge the mud wall above Moon. Having something to do in such situations helps contain my fear. My shutter whirs as a projectile from Moon's weapon makes a distinct “plunk” sound, followed moments later by the crump of the explosion.

Brennan’s Marines kneel in the middle of the lane and fire up the alleyway, drawing return fire. Moments later, a volley of .50-caliber rounds from the Marine sniper’s Barrett M82A1A SASR rifle whooshes over our heads. The Taliban machine gun falls silent. Another nearby squad team of Marine Snipers manoeuvres to hunt the insurgents, but as usual the Taliban have vanished like ghosts into the warren of compounds and alleyways, hauling their dead or wounded away with them. All they leave behind are the metal casings of spent bullets.

▼

ambushed

ambushed

Sgt. Brennan

November 1, 2010—I order LCpl. Roche and LCpl. Orr to bound ahead to the next alley and they take off under our covering fire. BOOM! The ground shakes. A cloud of dust and smoke rises from Roche and Orr’s position around the corner, just out of sight. The shooting stops and suddenly, quiet. Fuck. Despite weeks of intense fighting and the constant threat of IEDs, none of my Marines have been hurt. Now I fear I may have just ordered two of my men to their deaths.

My squad is flanked by Taliban. Marines are trained never to give up ground. We have to keep pushing forward. The only way out is for us to fight. We’ve never been this deep into this city before. With every pull of our triggers, our supply of ammunition is depleted. We have no reinforcements. We have no resupply. The closest Marines would take fifteen minutes by vehicle to get within reach, but we’d still have to fight our way through half a mile of narrow alleyways to get to them.

Rounds kick up dirt along the walls and hiss overhead. Fire is incoming from three directions. We are nearly surrounded. Whether it was intended or not, we’ve been lured into the very attack and counter attack scenario we were hoping to deploy against the Taliban. The puzzle has shifted.

▼

Blast concussions & TBI

Blast concussions & TBI

The Explosion

The blast from an RPG warhead forms a ring of death: anyone inside a twelve-foot radius will likely be torn to bits. Those outside the circle are still vulnerable to flying shrapnel and the invisible force of the blast wave. The power of the explosion decreases almost immediately as it moves away from the epicentre, but at close range, the blast wave can crush bone and amputate limbs. Further away, it inflicts less visible damage. It's movement through human tissue is enough to force gas pockets inside the body to contract and to send blood and fluid sloshing into spaces that are normally empty. Organs can be knocked out of place.

The organs most susceptible to such a pummelling include the inner ear, the lungs and the brain — that three pound mass of fat and protein that makes us who we are, and that responds most poorly to hard hits. When the shockwave from the RPG ripped through the delicate wiring of Brennan’s brain, it was like a baseball bat smashing into a computer circuit board.

More than a quarter million U.S. service members have suffered traumatic brain injuries. The injuries and symptoms range from mild – such as language, balance and mood problems – to severe debilitating brain damage. If treated early, and properly, sufferers can experience varying degrees of recovery. Our understanding of blast injuries and traumatic brain injury — the signature wound of modern warfare — is in its infancy, but all the research indicates that those with a TBI are far more likely to succumb to depression, PTSD and suicide.

▼

post traumatic stress

post traumatic stress

The Numbers

Of the 2.7 million U.S. service members who served in Iraq and Afghanistan, nearly one third of them suffer from post-traumatic stress. In other words, recent wars have created 500,000 mentally wounded American veterans. The military stigma surrounding mental health means that only half of those who report problems actually seek treatment. The Department of Veteran Affairs has proven dysfunctional and systematically incapable of providing essential care, leading to soaring suicide rates. Every 24 hours a member of the military commits suicide. Every 80 minutes a veteran does the same. Nearly one in four suicides in this country involves either a veteran or service member. This military's problem of post traumatic stress, brain injuries, and suicide has become a burning national issue — one that will only grow more critical after a decade of constant war.

Help

Crisis Line for veterans and active duty members 1-800-273-8255 press 1 Suicide prevention

▼

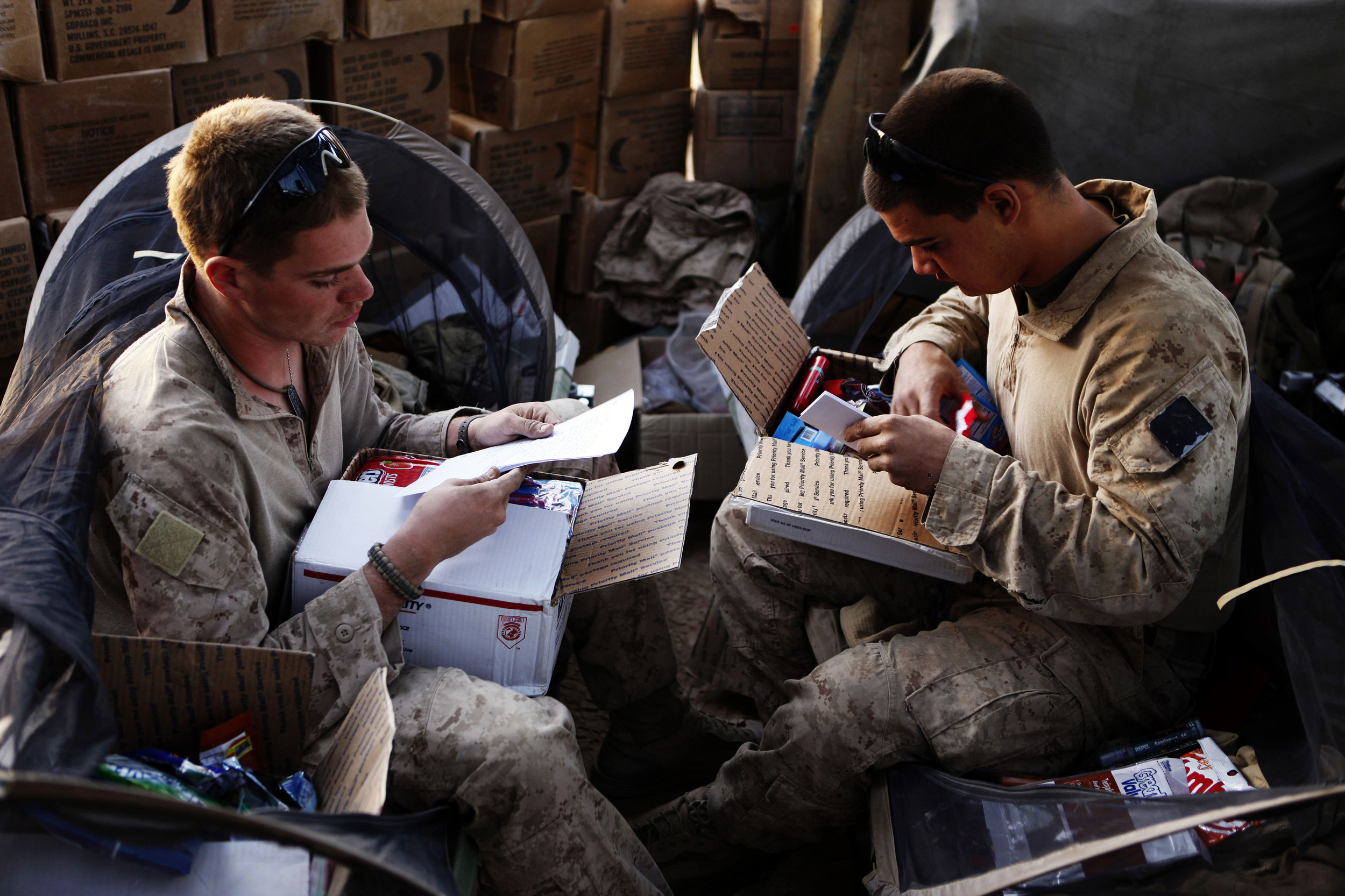

the squad

the squad

Third Platoon, Fourth Squad, Able Company, First Battalion, Eighth Marines

▼

Afghan forces

Afghan forces

Security

Since the withdrawal of coalition forces from Afghanistan in late 2014, the Afghan National Army and Police have assumed responsibility for securing the country.

▼

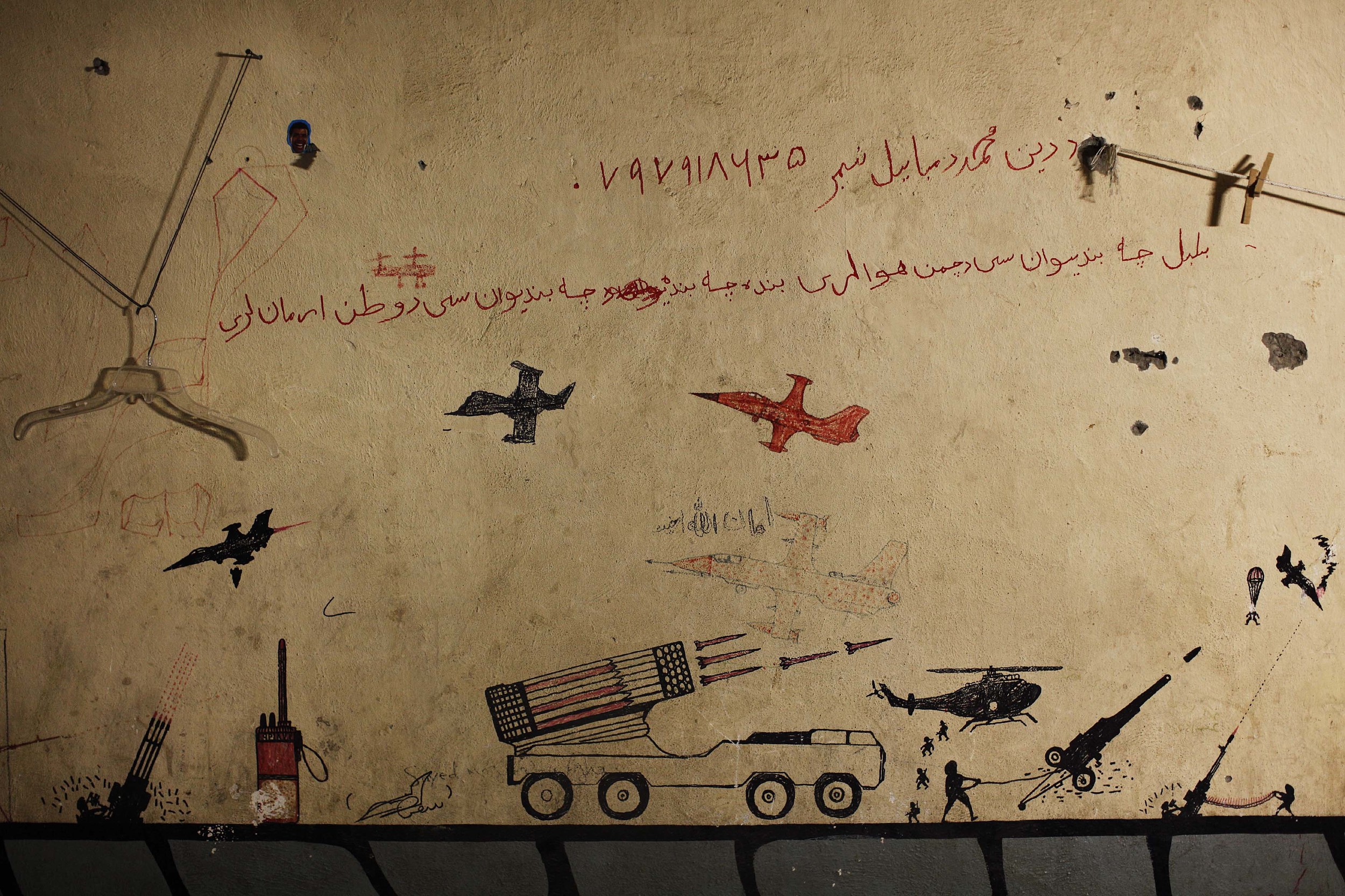

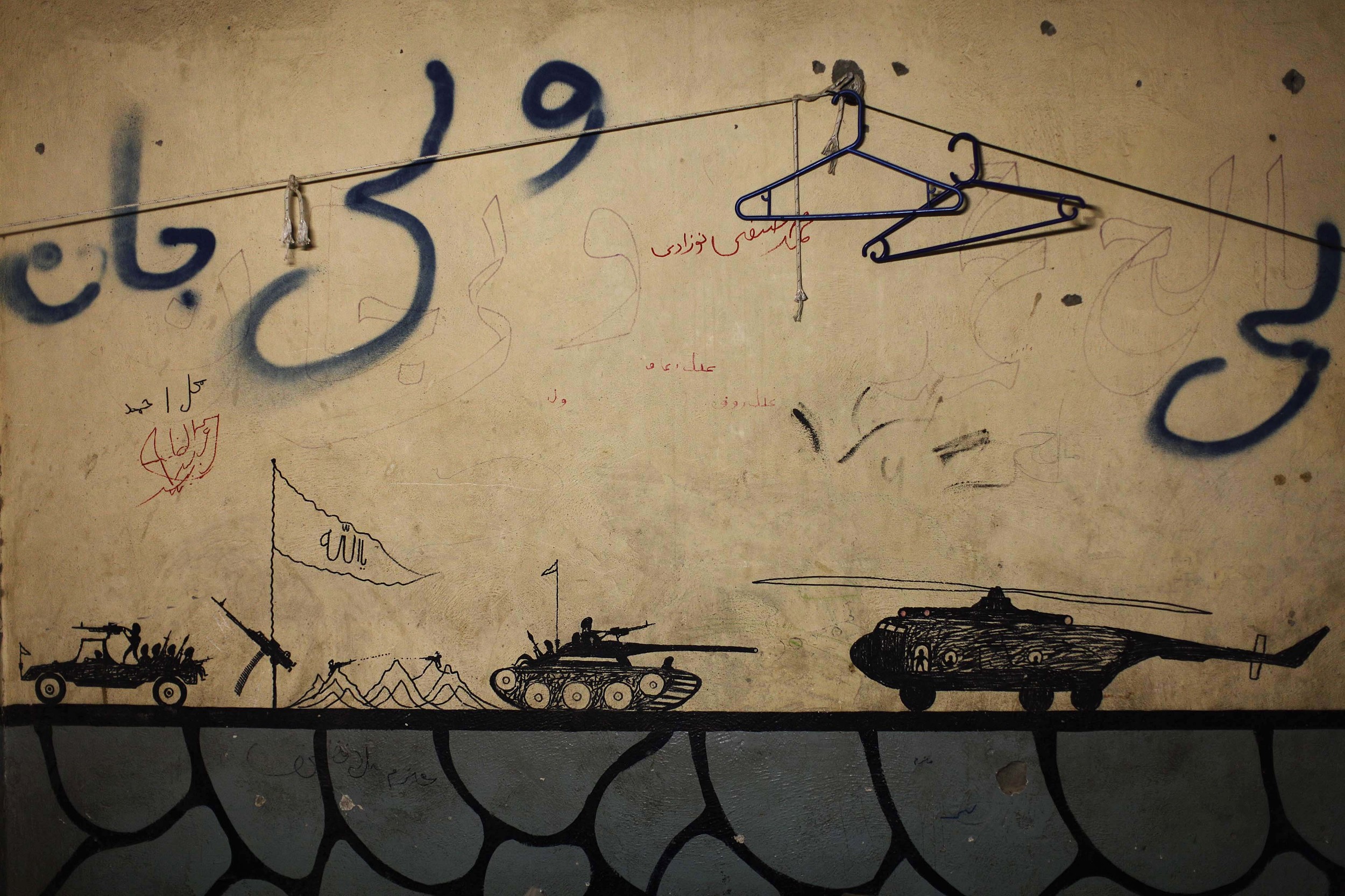

Taliban

Taliban

Still Strong

Musa Qala, the dusty and impoverished district of northern Helmand province where Sgt. Brennan and his squad served, fell back under Taliban control in August, 2015. The strategically-important sector was hard won and saw some of the fiercest clashes between Western forces and the Taliban following the American-led invasion of Afghanistan in 2001. Taliban graffiti shown here was scrawled on the walls of the District Center, which was under control of the insurgents, then the British, followed by the Americans, before the Taliban took it back in 2015.

▼

Afghan civilians

Afghan civilians

War's Toll

The total civilian death toll after more than a decade of war in Afghanistan is almost 18,000. More Afghan civilians were killed in 2014 than since 2009, according to the United Nations. While Nato has ended its combat mission, and Barack Obama has declared that America’s longest war is ending responsibly, fighting in the country is intensifying.

A UN report documented 3,699 civilian deaths in 2014, the highest death toll since the agency began keeping systematic record in 2009. Another 6,849 people were injured, bringing the number of civilian casualties to 10,548, a 22% jump from last year. Children were the hardest hit: 714 were killed and 1,760 wounded, an increase in of 40% on 2013. In addition, 298 women were killed and 611 injured.

▼

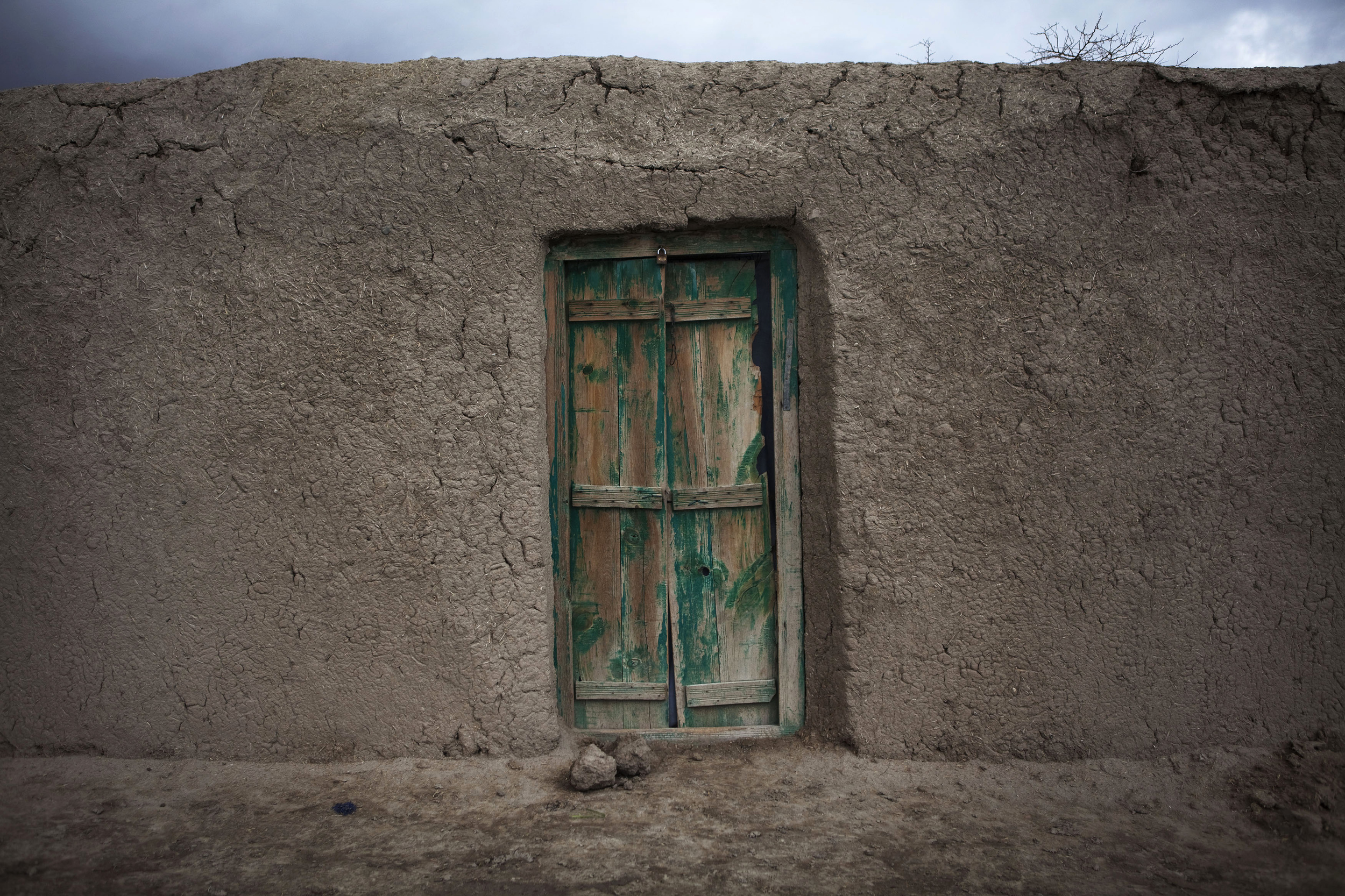

Afghan doors

Afghan doors

A Splash of Color in the Desert

These doorways symbolize the closed nature of Afghan society, as well as the fact that United States Marines are tolerated by the local population, but not welcomed. I suppose, in some way, they also reflect my own frustration about not having access to the people of Afghanistan while on military embeds. Photographing doors allowed me to imagine the hidden world behind them, to paraphrase a line from Baudelaire’s poem Windows: Looking through an open window a man never sees as much as when looking at a closed window. -Finbarr

▼

Canadians in Combat

Canadians in Combat

Kandahar

Canada paid a heavy price for its Afghan mission. One hundred and fifty-eight soldiers, two civilians, a diplomat and a journalist were killed. More than 1,800 Canadians were wounded. The war cost Ottawa at least $18-billion – and much more if the cost of caring for veterans and their families is included.